Argylls Remember: The Last Word

Introduction

This post concludes the Argyll Regimental Foundation’s special project for commemorating the 75th anniversary of the end of the Second World War. The month started with reflections, published in Black yesterdays: the Argylls’ war (1996), with selections from the chapter “The Wounded and the Dead.” Each day we have published at 1100 hours the Argyll poppy text for at least one Argyll killed in action during that conflict. The Argyll poppy project itself shall continue but not on a daily basis. More will be added in the months and probably years ahead. But this year’s month of Remembering Our Fallen ends with today’s post.

This post originates in the final weeks of finalizing the manuscript for Black yesterdays. The book is admittedly an unusual one and was planned as such. It originated in a discussion with Brigadier General Doug Fearman in the fall of 1984. We were standing at the bar in the snug of the Argyll Officers’ Mess. We had concluded successfully a summer project in which senior undergraduate students interviewed Argyll veterans. The “General,” as we called him, told me that the veterans wanted something to come out of that effort. I was slightly intrigued and inquired as to their specific request. As it turned out, they wanted a book but “something different.” The concept was amorphous but its direction clear. BGen Fearman had already made up his mind that something different would be done; he also believed he was looking at its author. He wondered what type of book would fit with their concept. I told him that most books fall into the historical narrative or historical analysis mode, and then there are books that are collections of documents primarily used for research purposes and not to tell a story. I wondered aloud about the possibility of a book that encapsulated the collective experience of the Argylls through their individual ones, as expressed in interviews, reminiscences, letters, diaries, poetry, pictures, cartoons, and art. In short, everything would emanate from the participants in the event who belonged to the 1st Battalion during the war years. Doug Fearman possessed a critical mind if he possessed anything, and he had a sharp, probing intellect. He wondered if anyone had done it before. To my mind, no one had, and that blunt response did nothing to dissuade him. I had just been volunteered for the task.

In the last stages of manuscript preparation in the spring/summer of 1996, every spare second was given over to the book or whatever it was – Capt Claude Bissell said once it was more akin to an epic poem, or so he thought. There were a number of last-minute decisions. I decided to add to the half-title page a full paragraph from Maj Paterson’s text containing the phrase “black yesterdays,” possibly in unknowing acknowledgement of, and homage to, Bissell’s direction to me in 1984 about the collective meaning of the Argyll experience. I thought of adding at the end a closing image of the battalion marching away, with the words “to-day has come, and … those black yesterdays are forever left behind” over it. LCol Rick Kennedy suggested that we fade the picture – we had found only one – to give it more dramatic effect.

And somewhere in those frantic days, I determined to provide an afterword and I had one in mind. As with everything else in the book, save for editorial notations, it originated with a veteran. Cpl Harry Ruch, when in hospital in England recovering, had written an epilogue to his own fragmentary diary. As he recuperated, he pored over it disappointed at, to his mind, its fundamental inadequacy to explain, let alone convey, the experience of battle. Moreover, the essential message of the epilogue suggested the futility at the heart of Black yesterdays itself.

I thought the world of Harry Ruch, a lovely man to be sure, and sought his permission to set off his work in the manner proposed. He offered no objection and we plunged ahead. One thing niggled. It was an afterword, but it needed something, we thought, more suggestive of its inherent qualities. A friend came up with “On the Morrow of His Battles”; our work was almost complete.

At the conclusion of this November’s project, it seems appropriate to offer up again Cpl Ruch’s insightful response to the nature of battle, his own wartime experience, and that of his Argyll comrades-in-arms.

Over to you, Harry, one more time for the last word.

Robert L. Fraser

Regimental Historian

P.S. It is important to thank the Board of Directors for the Argyll Regimental Foundation for its support of this project. Col R.D. Kennedy and LCol Tom Compton, two of my closest friends, have offered continuous encouragement, as have Col Jim Ruddle, who recruited me in 1980; Capt the Reverend Dr Alan McPherson; and LCol Garry Sexton. Lt Alan Earp, who commanded the Pioneer Platoon from November 1944 to 14 April 1945 (when he was wounded at Friesoythe, Germany), has provided critical commentary as I pondered elements of certain battles, especially Veen, and a wide range of other topics. He graciously provided the introduction to the first posting on 1 November – thank you, Col Earp. It was a collective enterprise to be sure, and in the book I thanked all of the people who worked on it save Lt John Ferguson, who quickly pointed out my terrible oversight. Lorraine M. DeGroote has been supportive of the Argyll poppy project from its inception and painted both the Argyll poppy and the Argyll Field of Remembrance. She has been a model of forbearance in the past several months as I devoted every spare second to Argyll poppy texts. For all of this and so much more, she has my thanks. Once again, members of the Argyll family have made such a project possible. The veterans had insisted on the rightful place of the Argyll fallen in the book. For the current enterprise, the families of the fallen have consented to interviews, often painful and tearful, and provided letters and images so crucial to understanding that sacrifice was familial and collective – thank you! Finally, ARF is indebted to our talented freelance digital editor, Julia Armstrong, who has worked faithfully and tirelessly over October and November – often at the last minute – to provide editorial commentary, placement of images, a template for the design elements, and other critical support. Thank you, Julia, for your talent and your loyalty. Albainn Gu Brath.

Death in battle is different, Sam Chapman thought:

“He is cut down in an instant with all his future a page now to remain forever blank.

There is an end but no conclusion.”

– Capt Sam Chapman, C and D Coys

Black Yesterdays: The Argylls’ War

On the Morrow of His Battles – An Afterword

From the time the Battalion went to France until his hospitalization on 20 Oct. 1944, Cpl. Ruch kept, as best he could, daily notes (without dates) of what had happened. When his unit was in a holding position, he tried to put them together. Then, in hospital, he attempted to establish some chronological order. Later, in England, he typed up his notes and destroyed the originals. “When I reread it,” he recalled, “it told only the bare essentials, not the human side.” And the bare essentials lacked any power to convey what battle was like. In an attempt to remedy this deficiency, Ruch penned this epilogue.

Private Diary. Epilogue. Cpl. Harry Ruch. 7 Platoon, A Coy

The foregoing is just a brief story of some of the main points of what happened and leaves many points untouched. In action situations are happening every second and every second seems an hour so only a small fraction of what happened can be catalogued. It will be noted that the term “a quiet and uneventful night” has been used quite often. This statement will prove misleading to the uninitiated as I refer to a quiet night etc. compared to the noisy ones we had been through. There was never really a quiet night at the front. One was always on the alert and expecting anything.Another term which will prove to be misleading is when I refer to “no opposition”[.] This should not be taken literally as it does not take into account the brief skirmishes with small enemy parties, rearguards and patrols which were constantly in evidence. It was just that it was not a heavy prolonged engagement like the Seine, Caen, Falaise, the Albert, etc but they proved to be very sticky and dirty and cause us almost as many casualties as the big ones. This type of fighting happened quite often.

This does not take into account the hours we lay in trenches sometimes for days never knowing what was to happen next, the tiring drive from Caen to Antwerp when we were on the go and alert from the 8th of August until the 20 October without proper rest. It does not take into account the many wet and cold nights and days when we went without a bath or proper wash for 6 weeks, without shaving for a week or more, without sleep, food and only a quart of water for 72 hours at a time.

It does not take into account that we lived, ate and slept in trenches. That we have seen our close comrades killed and maimed for life, we have seen our comrades crack and go to pieces, have experienced the sickening smell of death and battle for days, have seen twisted and broken bodies of our own and enemy men. Bodies that lay in the open for days.

It does not take into account the effect on a man’s mind when he lays for hours under a bombardment, never knowing if a shell will hit his trench next, hearing the cries of his comrades who have been unfortunate. It does not take into account the effect on a man’s mind going into the attack with shells dropping amongst his Coy, seeing his men fall.

It does not take into account the bodily weariness that comes from continually being on the alert and driving hundreds of miles in pursuit of the enemy. That is something that cannot be put on paper and must be experienced by the reader before he can understand.

It may seem that we did not have some good times. To give that impression would be misleading. In action one has the very close comradeship of men who have submerged all their petty and selfish differences. They are rather out of place amongst the death and destruction of war. Here, in every day happenings men performed what would seem like heroic deeds in civilian life and which were natural and seemed insignificant. Men risked their lives to save a comrade, went out of their way to help others. We were soon able to receive enjoyment and fun out of things that would not interest the average civilian. We took our fun when we could as we never know what would happen next.

The old saying “Eat, Drink, and be Merry as to-morrow you may die” was never truer out there.

During the Second World War, the 1st Battalion, The Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders of Canada (Princess Louise’s) had 288 killed, 808 wounded, 72 prisoners, and over 200 who left the battalion as a result of sickness or accident. The total is 1,368; about 3,300 served during the war; the casualty rate is 41.45%. The battalion went into battle in July 1944 with just over 800 men; its fighting strength was about 400; it lost that strength over 3 times during the course of its 11 months in battle – black yesterdays indeed!

“a history bought by blood” – Capt Sam Chapman, C and D Coys

Robert L. Fraser

Regimental Historian

Cpl Harry Ruch, 7 Platoon, A Coy.

Cpl Harry Ruch, 7 Platoon, A Coy.

Harry and Lillian with son Bruce.

Harry and Lillian with son Bruce.

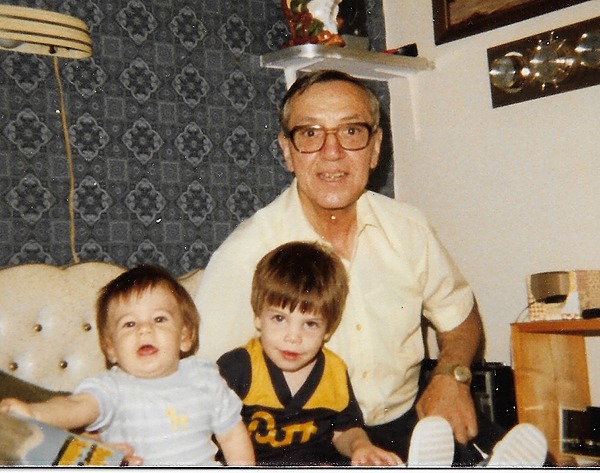

Harry with grandsons Michael and John.

Harry with grandsons Michael and John.

Harry and Lillian Ruch, 50th wedding anniversary, June 1997.

Harry and Lillian Ruch, 50th wedding anniversary, June 1997.

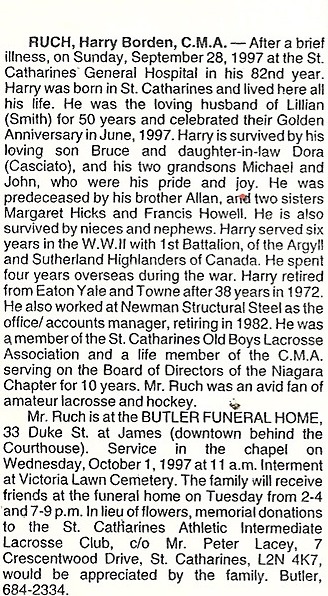

Cpl Harry Ruch’s obituary, 1997.