Pte Joseph Carlton (B 46042) (1920–44)

Introduction

Many of the Argyll KIAs have been known to me since the 1980s. Most often, my acquaintance resulted from conversations with Argyll veterans such as Pte John “Mac” MacKenzie. I learned of others through letters and diaries. Joe Carlton was different. We were in the last stages of preparation for Black yesterdays and learned about his widow from another Argyll veteran. One of the staff had a memorable interview with Edna Bates. Not only did she provide some of Joe’s letters for use in the book, but she also wrote several pieces that we used. My recollection of his description of his visit with her remains vivid. A composed and dignified woman with an acute intelligence, she spoke warmly about her first husband and evocatively about their young life together during a time of war, in a forthright manner. At the end, she saw the interviewer to the door. Just as he was leaving, she said with tears streaming down her face that “there hasn’t been a day since he died that I haven’t thought of him.”

Robert L. Fraser

Regimental Historian

“He is cut down in an instant with all his future a page now to remain forever blank.

There is an end but no conclusion.”

Capt Sam Chapman, C and D Coys

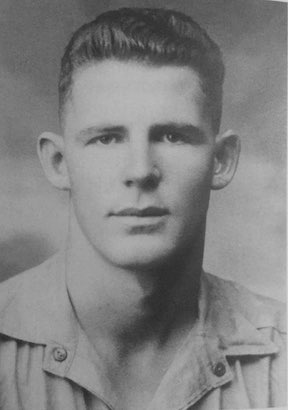

Joseph Carleton was born in Toronto on 11 March 1920; his parents, Joseph Carlton (1887-1945) and Sarah “Sadie” Wilson (1885-1946), were married there on 19 October 1917. Carlton’s family had emigrated from England about 1908 and lived in Toronto, where he was a fireman and joined the militia. He enlisted in September 1914, went overseas with the 4th Battalion, and was wounded at Langemarck on 29 April 1915; he was subsequently discharged as medically unfit. Tall and fair, Carlton had a “tattoo of a boxer on his forearm.” He returned to Toronto, where he met and married Sadie Wilson, a waitress who was born in Belfast.

“to help his mother support the family”

The Carltons lived in York region, where their four sons were born. About 1926, they moved to Grimsby. As Joe’s widow, Edna Jeffrey, told it: “At the end of Grade 8 he left school and went to work on a farm, to help his mother support the family, as she was bringing her four boys up alone …” He worked in a greenhouse and then on a road gang for the T.H. & B. Railway for one year. Carlton moved to Hamilton three months prior to his enlistment with the Argylls on 18 July 1940. He had no previous military experience, and after the war, he hoped to be a steamfitter. “He felt,” Edna wrote, “that it was his duty to go.” Moreover, she added, “he had part of his pay sent to his mother.”

“it was his duty to go”

Canada’s participation in the Second World War affected the country collectively and Canadians individually. “He gave me an engagement ring at that time. This wasn’t a traditional ‘war romance.’ We had gone to Sunday School and Young People’s meetings at Rock Chapel Church [near Hamilton] for years together.”

“wasn’t a traditional ‘war romance’”

Initially, the Argylls remained locally: Hamilton, the Niagara peninsula, and Camp Niagara at Niagara-on-the-Lake. Perhaps that explains the couple’s decision “to postpone marriage until after the war.” Matters changed while the Argylls were in Nanaimo, B.C., from May to August 1941. Carlton was promoted acting lance corporal on 29 May 1941, three days after the battalion had arrived at Camp Nanaimo. “However, when Joe was with the regiment at Nanaimo B.C., he wrote and asked if I would marry him when he had his leave, which was to be in that summer, 1941. I agreed, and we began to make our plans by letter. Then he wrote to say the regiment was coming back to Niagara-on-the-Lake, en route to – he knew not where. Could we ‘speed up’ plans, as they were to get here on Aug. 18 or 19?”

Other ranks in the army required official permission to marry and Joe Carlton was no exception. Maj Rob Roy, OC of C Coy, signed the permission form for Joe to marry. Friends of Edna’s family had attested to her suitability and Roy accepted it. Edna “wrote back, agreeing, and had a one-week rush to make my long white wedding dress + slip, satin pyjamas, and a suit of Sutherland tartan, his regimental plaid. I got them all done on time.” There were problems, however: “Aug. 18 came – but no Joe. On Aug. 19 I received a letter saying the plans were fine, but I forgot to tell him the date! Obviously I didn’t re-read my letter.”

“our minister was on holidays”

To make matters worse, “Our minister was on holidays, … so we had asked a former minister, about 30 miles away, to marry us. He came up about 10 am. He asked if I had the license. I said I expected Joe would get it, but he said you had to get it where you lived! So I rushed up to the City Hall in Hamilton, about twenty miles away, only to find I must have a birth certificate for Joe, since he wasn’t there. I hurried back to get this from his mother [in Grimsby], but she said she hadn’t one. She went back with me, but on the way up we went by Standard Barracks, and the regiment was in! So Joe went with us to get the license.”

In good military fashion, Joe and Edna improvised (and overcame) as one marriage plan gave way to the next:

“Instead of 2pm, as first planned, or 7 pm, the next plan, we finally were married at 8 pm! The 24 hours pass meant Joe had to report at 10 am the next day. He was given a 48 hours pass. When he asked if he could have a longer time because he got married the night before, the officer said, “You certainly didn’t waste any time!” He marked out 48 and put in 72. That almost got Joe picked up by the military police! All that saved us was the marriage certificate which our friendly minister suggested Joe should carry.”

“not want me to have to bring up a family alone”

For the Carltons, there were other considerations, serious ones that would not have come to the fore had it not been for the war: “Joe did not want me to have to bring up a family alone, if he should get killed. So we went to the doctor for proper birth control…”

The young couple had just a few weeks together in Vinemount, where Edna now lived; they had scant time together before the battalion was off again, this time for Jamaica. With separation the only constant in their lives, Joe Carlton took steps to include Edna in the daily contours of his life and to assure her of his constant love: “Joe was at Niagara-on-the-Lake for a short time before he went to England. He wrote almost daily, sort of a running diary of his life, and mailed it when the “airgraph” was full. Each letter was full of love, and looking toward the time we could be together to stay.”

“He did the best he could every day”

On 2 September the unit left for Jamaica and did not return until the end of May in 1943. Edna reminisced that Joe was “Unselfish + generous – He saved all the money he could in the army + sent it home to save for our future, rather than spending it on himself.” Joe had a “Sense of humour – He was fun to be with. Everyone who knew Joe liked him, and he made things happier + better when he was around…” Their time apart was marked by mutual trust. To her, he was “Loyal and faithful, trusting: He never lost his loyalty to me, no matter how far or how long he was away from home. He never doubted my fidelity, nor gave me any reason to doubt his. He did the best he could every day, wherever he was, but lived for the time the war would be over and ‘we could begin our lives together,’ as he said.”

During the years and months apart, letters and parcels expressed their love and their bond. From Edna’s perspective, Joe was always “Appreciative … He never forgot to thank me for every article he received in a parcel. He commented on which were his special favourites, when he ate them, who he shared them with, and so on.”

“The roles of a soldier are many”

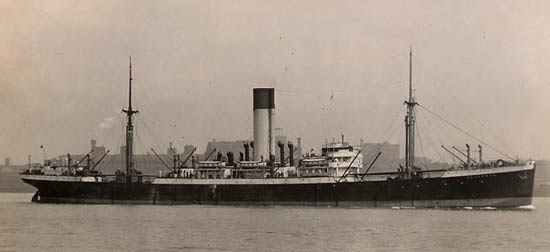

In Jamaica, he reverted to private on 23 January 1942 because of his one and only misdemeanour as a soldier – “failing to report an absence.” On 23 March 1942 he was detached from the unit on “special duty” and reattached on 27 May 1942. “The roles of a soldier are many,” wrote Lt Bob Paterson. He and the “fourteen Other Ranks [including Carlton], who accompanied him, have ample reason to verify this statement.” A British-registered ship, the Agapenor, “lay at the mouth of the Panama Canal” “deeply laden with Malayan products.” During passage of the canal, “trouble arose between the Chinese crew and the Ship’s officers.” Americans maintained order while “waiting for a British guard to accompany her to Halifax. Hence Lieut. Paterson and his fourteen men.”

The guard, or “Agapenor detail” as it was called, obtained passports and civilian clothing. “Decked out in white suits and sporting hobnailed army boots” and with army packs loaded with weapons, they flew by Pan American clipper to Barranquilla, Colombia, before another trip to the boat. On 23 March, Paterson and a portion of his detail were relieved by Lt Alex Logie and more Argylls, including Carlton. They acted as guards as the ship sailed – uneventfully as it turned out – to Halifax. Whether Joe Carlton received leave in Halifax to return home or not is unclear.

Two of Carlton’s brothers also served. His brother Jack was with the RHLI and taken prisoner at Dieppe on 19 August 1942 (the Carltons’ first anniversary). Badly wounded, he died in a POW camp in Germany. In August of the following year, Joe’s older brother Jim was shot down over Germany and was a POW till the end of the war.

“a reliable and steady soldier”

After the 1st Battalion returned to Camp Niagara from Jamaica on 26 May 1943, the army interviewed all prospects for overseas service. Joe Carlton was 6’, 175 lb, in “good health,” with brown hair, hazel eyes, and “good” development. The personnel officer described him as: “Neat appearance,” a “smart man with [a] good degree of intelligence.” He deemed his “Stability and deportment sound,” adding that he “Appears to be mentally alert and keen but lacks ambition. Seems to be a reliable and steady soldier.” All in all, he was “Well suited for present employment [a Bren gunner in C Coy]” and “satisfactory for overseas service.”

The unit gave Carlton a furlough in June and then nine days of private leave in August, his first time with Edna since 1941 – it would be his last. Overseas, the unit received its new commanding office, Lt-Col Dave Stewart, in September 1943 and underwent more intensive training at all levels and in different places. Joe Carlton was in C Coy and wrote to Edna whenever he could. On 18 July, just days before the move to France, he wrote: “Well darling I have been in the army four years to-day. It seems like a long time. I only hope it isn’t 4 more…” Four days later, he scribbled a few more lines:

“I’m writing in an awkward position honey but I guess you’ll be able to read the writing anyway. I haven’t had a chance to write since Tues. [18 July] and I may not get another chance for a few days. I’m going to send this as soon as I run out of conversation (which won’t be long), it will be a letter anyway and it will let you know that I’m still O.K. It has been a rather nasty day to-day. It rained this morning and it is still cloudy and cool. It may rain again but I hope not. The last letter I got from you was on July 14. I guess by the time I write my next letter to you I’ll have another country added to my list…”

On the 25th, he added another country to his list; he was in France:

“I wrote my last letter to you on board ship honey, I finished it off last Sat. I was on the ship quite a while but I didn’t travel very far. The water was very calm and I wasn’t sick at all. The meals were a little different than we have been used to, they were quite good. We had an issue of a few hard candies and one chocolate bar and 7 cigarettes daily. I gave my cigarettes away. I slept on deck all the time I was on the ship. It rained one night. I slept in one of the crews mess’ [sic] that night. I had my first bath in France this after-noon, in a deep creek, the water was quite cold. The day hasn’t been so hot either. It is cloudy and quite cool. I’m writing in a small apple orchard honey, there is a couple of old frenchmen [sic] hoeing in a garden next to the orchard.”

“I wish I was there right now beloved instead of lying in a field”

Carlton seized every moment to write about the small details of daily life as the battalion waited to be sent into the line. Food was the primary topic of his letter on the 26th. It also occurred to him that he would much rather be lying with her at home than in a field in France:

“…I have made my own meals since last night. We get a dry ration, it is oats pressed in blocks and stuff that is supposed to be meat, tea and dryed [sic] milk pressed into cubes, 3 chocolate bars and candy, it is supposed to do for 24 hours. It isn’t very appetizing (that isn’t spelled right I don’t think) you know what I mean anyway. The weather is quite warm and I guess I’m not hungry. I haven’t done much to-day honey … I wish I was there right now beloved instead of lying in a field (Somewhere in France) writing to you…”

“fairly fresh graves”

As the Argylls advanced to the battlefield, the signs of war were everywhere. Joe saw Caen on the 29th – “It is really a mess.” There was the rumble of heavy guns [Allied] firing in the distance.” As they marched through small villages, he observed “most of the towns are taking quite a beating though.” There was another looming reality on the horizon: “I guess I’ll be seeing a little bit of action after a while…” The images of battle were accompanied by the face of battle – death. On the 31st, he wrote:

“I’m lying in a bit of a hollow writing honey. There is a “knocked out” Jerry tank about 10 yds to my left. It is really burnt out and “busted up”. Up on the top of the bank is a couple of fairly fresh graves. I haven’t looked at them close but some of the fellows say it is an officer and a private (ours). There is a dead German down the line a bit. I haven’t been to see him either, the fellows that have say that he should have been buried some time ago.”

During the night of 31 July/1 August, the Argylls marched to Bourguebus, almost 800 yards from “the nearest enemy position, held in great strength” – Tilly-La-Campagne. Cpl Douglas Rathbun , C Coy, had a searing memory of it:

“…we got in there … he [Lt Sloane] called me over and he says, ‘Tonight, you’re taking a patrol out.’ Holy Jesus, I knew I was in the army and so I had to take my section out … left around eleven o’clock … and we were supposed to go … across this field to a certain place. And we thought we were doing right and then Jesus, I went back to my Bren gunner, Joe Carlton, and I said, ‘Geez, I think we’ve gone too damn far’ – and we were … I says, ‘I don’t think we’ll go any further.’ And we were scared because the artillery was coming down. So we did go up, cut across … and I knew where I had to meet another regiment and report.”

For the Argylls, the experience of battle descended upon them swiftly in the heat and dust of early August. The shelling was “horrific” and “constant” as well as mortars, strafing by aircraft, and sniping. The town itself was “a shambles.” CSM (C Coy) George Mitchell’s diary entry for 2 August recorded “Shelling still terrific – difficult to move around.” With battle came the inevitable casualties. For Padre Charlie Maclean, “I had to go out and bury them … we’d just bury one” and then “be hit by shelling so I dove in the grave beside the [dead] fellows, who were pretty high … And I thought to myself, ‘Well, you did your darndest to get into this business. Now put up with it…’”

“Your loving lonelier than ever husband Joe.”

Over the next few days, the action intensified. Carlton wrote his final letter to Edna on 3 August:

“I didn’t write to you yesterday honey. I was in a slit trench last night and the night before. I manage to get out of the trench once in a while but I never get too far away from it. It reminds me of a ground-hog honey. They bask in the sun and whenever there is any danger they dive into their hole. I think I have all the ground-hogs beat for speed though honey. I’m usually up quite a bit during the night but I get some sleep during the day so I get enough sleep. I have cleaned my teeth once since I came out here. I haven’t had a wash or a shave, I think I’ll grow a beard and take it home with me honey. We have to go easy on our water. The meals have all been cold but they are quite good. The weather has been favouring us with a dry spell. I hope it stays that way. Some of the fellows said when they wrote home that they told their people they were in France but they never mentioned action. Well I don’t know whether I’m doing the right thing by telling you or not but I think you would rather know than have me hold out on you … I only hope this doesn’t last much longer and that we can soon be to-gether and live our lives the way we want to. Good-bye for now beloved. I love you Edna. Your loving lonelier than ever husband Joe. XXXXXXXXXXXX”

Fifty or so years after the war, Edna characterized Joe as “Brave + uncomplaining. He did not complain about anything in the army, no matter where he was … He did not suggest he was afraid of the present or the future, though the former was dangerous and the latter very uncertain.”

At 1900 hours on 5 August, C and D Coys of the Argylls attacked Tilly supported by C Squadron of the South Alberta Regiment. “The attack,” the war diarist recorded, “was received by intense enemy shell, mortar, and small arms fire. The forward elements penetrated the town, but when it became obvious that further progress was not possible, the force withdrew. Casualties suffered were twenty-four, among them Lieut. Gordon Sloane [Carlton’s platoon commander], who was killed while attacking an 88mm. position. Four S.A.R. tanks were knocked out.” It was a grievous day in terms of losses; the worst to date; the first of many to come.

“Missing in action”

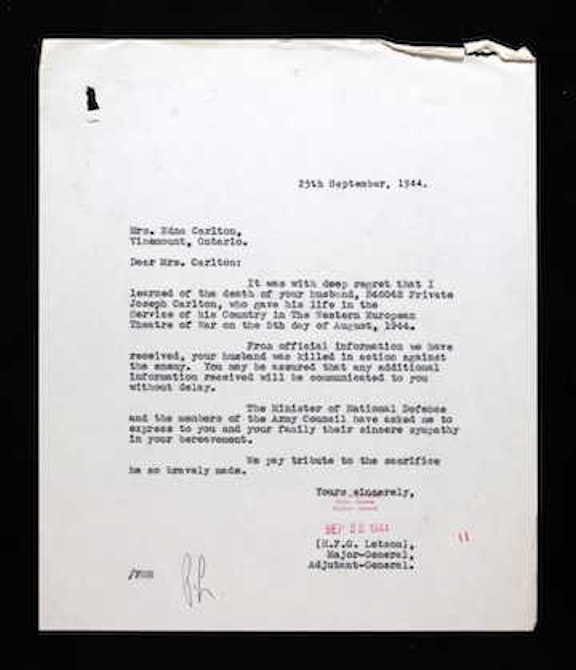

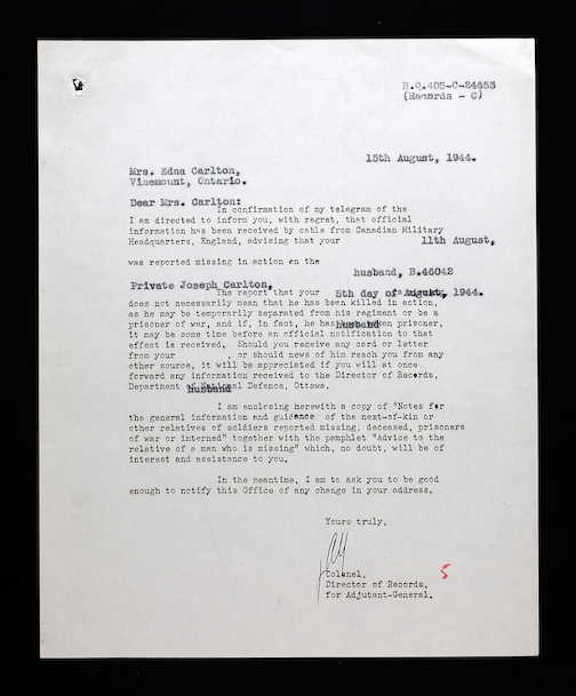

Edna Carlton received, as did many of the next-of-kin of Argylls killed that day, a telegram advising that Joe was missing in action. For Edna, there was hope but pervasive dread in the period between receipt of the first telegram and then the life-shattering second one. It was harrowing: “The first telegram, received on Aug. 11, said ‘Missing in action.’ The next two weeks were the longest in my life – a teeter-totter between hope and despair! On August 25, the second telegram removed the hope. He was ‘Killed in action August 5.’”

“Killed in action”

The second telegram altered her life forever and she handled it in her own way: “In the next weeks well over 50 letters and cards of sympathy arrived from friends and relatives. Official ones from George Drew, Vincent Massey and King George VI came also. One of the things Joe said in one of his last letters remained in my mind: ‘If I don’t come back, I don’t want you to mourn for me the rest of your life.’ I tried to go ahead and live so I thought Joe would have been proud of me if he knew. My mourning was done privately.”

“Joe was the best all round man in the battalion.”

In an undated letter, acting Maj Bob Paterson, C Coy, wrote to Edna:

“…I have known Joe since 1940 … The whole battalion knew Joe, and he was endeared to all by his steady, calm, pleasant, clean way of life. In my opinion he was the perfect example of a soldier. I am not telling you anything but the truth when I tell you these things – Joe was the best all round man in the battalion. “C” Company feels it as a deeply personal loss. We have been friends for a long time and it is terribly hard to have things broken up in this way. We all send you our deepest sympathy…”

Other Argylls retained their memories of Joe. Pte Jim Doyle, Scout Platoon had spoken “to Joe about half an hour before he went into [the] attack. Now Joe was a big, good looking, nice guy: didn’t smoke or swear; one of them nice people; a gent.”

Pte Carlton’s death in battle fractured his wife’s life. For her part, Edna displayed resolve and daily courage in facing the life ahead with stylish dignity, firm purpose, and an enduring love.

“[It] wasn’t easy to see all my friends marrying and having their families, when I had lost both my husband and the children we wanted. However, bitterness would not have helped me, or honoured Joe, so I tried not to question, ‘Why me?’ I joined the Red Cross Corps Transport Section in 1945, and drove out of Hamilton. This was a volunteer job, of course.

“I met the Regiment when it came home in 1946. It wasn’t easy seeing all the happy families reunited, and going home alone. When I got home, I was told Joe’s mother was in West Lincoln Hospital. They had called for me to go down. She had been taken there by ambulance that morning. But she died before I arrived – of pneumonia, they said. But I always had the feeling that she died of a broken heart. If Joe had been coming back that day, she would have lived – and had a reason to live.”

Edna Carlton remarried, as did many, if not most, Argyll war widows. Her sister had a baby boy in 1946 who was named Joe Carlton. After the accidental death of her sister, Edna Bates and her new husband adopted the baby. Her words are Joe’s epitaph:

“The world lost a very special person when Joe was killed – and so did I.”

On 4 and 5 August, 19 Argylls were killed in action, 17 wounded, and 1 POW.

Pte Carlton’s Argyll Poppy is in the Argyll Field of Remembrance: left cluster, bottom grouping, poppy at 1400.

“a history bought by blood”

Capt Sam Chapman, C and D Coys

Robert L. Fraser

Regimental Historian

Letter from the Adjutant General to Edna Carlton, 25 September 1944.

Letter from the Adjutant General to Edna Carlton, 25 September 1944.

Letter from the Director of Records to Edna Carlton, 14 August 1944.

Letter from the Director of Records to Edna Carlton, 14 August 1944.

Rock Chapel Church, near Hamilton, where Joseph and Edna attended Sunday school and young people’s meetings.

Rock Chapel Church, near Hamilton, where Joseph and Edna attended Sunday school and young people’s meetings.

The Agapenor was built in 1914 and sunk in October 1942.

The Agapenor was built in 1914 and sunk in October 1942.